Stoa Daily Challenge #14

Wish to learn practical supply chain concepts within the context of a realworld challenge? Well, here's your chance to learn more about how B2B logistics and operations work.

Help Pramit, Operations Manager at Udaan, optimize their return process.

Play the challenge here.

Now, to today's issue.

_____

‘Tis the time of year when we eagerly look forward to sharing our Spotify Wrapped lists on our socials.

But last year this time, other than the Spotify Wrapped, my Twitter timeline was full of Wordle bricks, and people keen to show off the number of attempts in which they guessed the word for the day. It was intense.

An eager beaver, I too jumped on the bandwagon and played the game religiously for about a month. It almost became a ritual without me having to put too much effort into building any habit. I guess it was the sense of accomplishment I got as soon as I finished the puzzle. The dopamine hit was a welcome change from the usual validation one gets by scrolling social media mindlessly.

Exactly what about wordle made it such a wild phenomenon, I wondered. I was intrigued by how its use became communal and ritualistic — two factors that so many mobile apps try really hard to perfect.

Here’s what I discovered:

The creator Josh Wardle had actually made a prototype of the game back in 2013 and dumped every five-letter word (about 13,000 words) in an endless play format. His friends opined that it was interesting but there wasn’t enough incentive for them to come back and finish the game. From the 13,000 words, there were quite a few obscure ones, which you could only guess using brute force. All the words weren’t accessible.

So, when Josh was building the game again for his partner during the pandemic, he reduced the five-letter words to about 2500 words that would be considered “accessible”. In an interview, Josh explained,

"There are around, I don’t know, 13,000 five-letter words. And we put a fair amount of effort into filtering those down into a subset of around 2,500 solution words that can be the solution any day. And the way we did that actually was I built another game before this one, which took all 13,000 five-letter words and displayed a word and displayed three buttons: “I know this word,” “I don’t know this word,” and “I maybe know this word.” And my partner, she just wanted a mindless game. She was going through some tough times. She just wanted something she could sit down and mindlessly do. So she categorized all 13,000 words."

And it worked! Simplifying the game didn’t make it any less challenging.

In fact, it led to what I believe is an interesting way to look at user-generated content (UGC).

UGC is a core marketing tactic, which builds trust in a business or a brand. Many businesses fail to get it right. What I think makes Wordle an interesting case here is that it designed complexity in a way that the users thrived on demystifying it. It got the users talking about how they were using the product and why it was an interesting way for someone else to adopt too.

Without any monetary incentives, it cracked the inherent need of humans to share something they felt they had uniquely discovered.

Twitter and WhatsApp were full of users communally sharing strategies of which strategy would solve the puzzle quickly. As soon as you cracked the puzzle you wanted to share how easily you cracked it. This directly fed into the communal aspect, creating a global virality around the word game.

In fact, the virality is so global that the game has a Bengali and an Arabic version, too!

Later on, one of the bigger turning points for the game was getting acquired by the New York Times (NYT).

Before we jump into why it made sense for the NYT to acquire the game, let’s first set some background.

Newspaper subscriptions have been falling since about 2006 and the proliferation of internet-based companies created other interesting avenues to document what’s newsworthy as is evidenced below:

"Eventually, niche websites removed the demand for newspaper-based classifieds while Google and social media eroded display advertising dollars. At the same time, free and easy access to online information drove a fall in newspaper subscriptions. This perfect storm meant that by 2012, newspaper advertising revenue was back to 1950 levels and the industry faced an existential threat. The NYT suffered along with the rest, and 12-month revenue fell 42 per cent in the 3 years from June 2010."

For those not aware, NYT is known for its crossword puzzles among a larger audience. In fact, they have a $40-a-year games package available behind a paywall.

Wordle players fall just right into the target category of customers who are likely to subscribe to NYT at least for the games package.

"At a $US3 million purchase price, the cost of Wordle could be recovered within a year if fewer than 10 per cent of daily players add an NYT subscription. Wordle players who don’t want a full subscription might still be attracted to the NYT’s Games package for $US40 a year. Anything in the vicinity of this cross-sell rate makes the deal a bargain for The Times. The tiny outlay has brought ownership of a social phenomenon and introduced another large global community to its universe of products."

A free game that users were hooked onto made it a lucrative top-of-the-funnel (TOFU) marketing tactic for NYT. The NYT nudges users to create a free account on the website in order to link and preserve their stats.

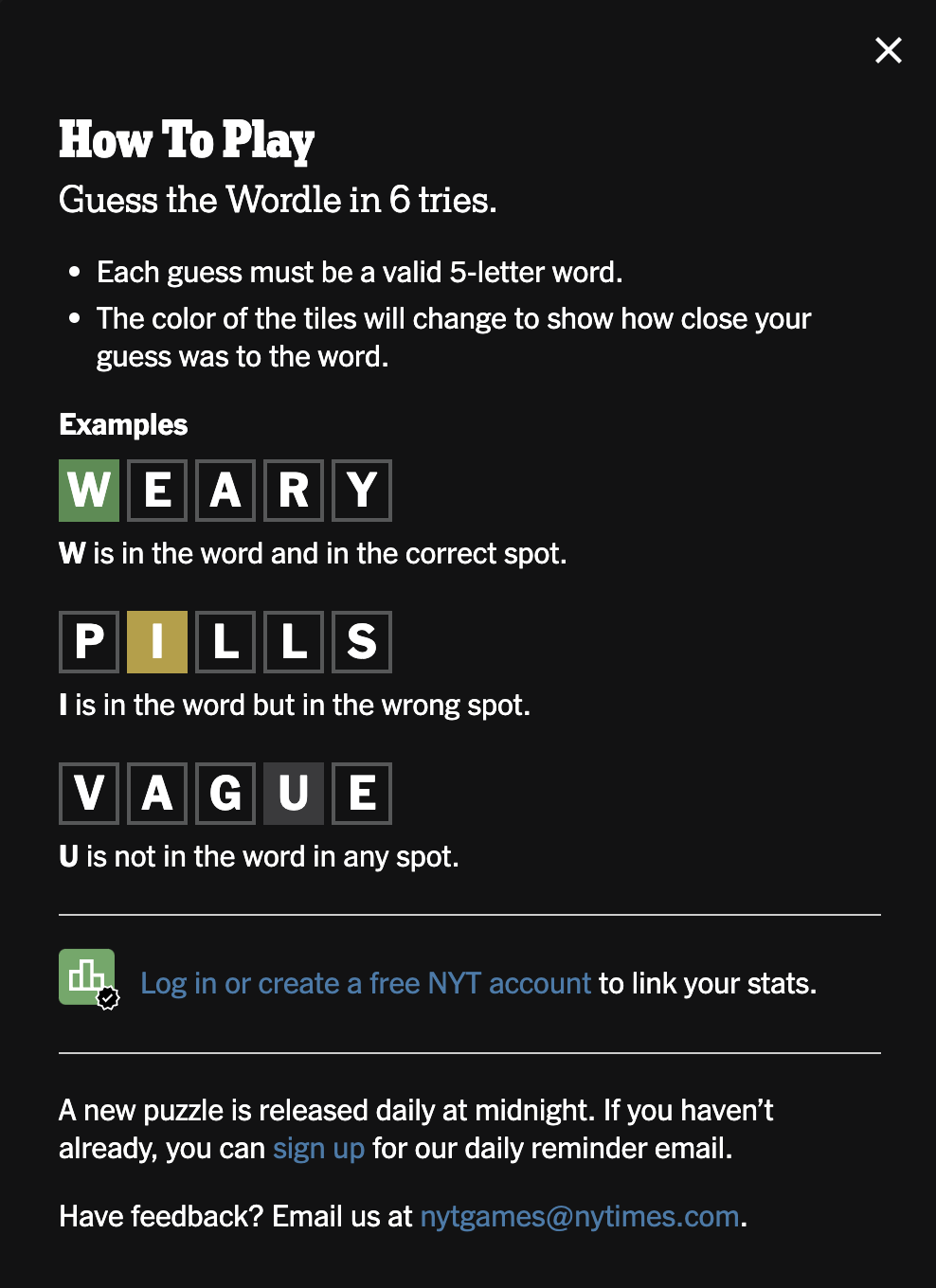

Notice how the CTA to create an account is casually inserted into both the intro screen as well as the result screen of the game. NYT has not drastically changed the game format or put it behind a paywall as was widely speculated but it has made accessing and sharing game stats conditional to creating an account on the NYT website.

Even if the game continues to be free, this TOFU activity has given NYT access to email IDs of a much wider audience it otherwise wouldn’t have tapped into. And leveraging the reach Wordle had organically garnered directly increased the reach NYT had. Here are some numbers that prove how the acquisition benefitted NYT:

Essentially, what is the larger business game being played here?

I feel the growth story of Wordle offers key insights on product-market fit achieved by making a lovable, easy-to-use, non-overwhelming product. Without farming for attention or adding any frills, the product serves the purpose of entertainment.

Now, I do understand that all products cannot be crafted in the same way but some learnings can be applied to create meaningful experiences for the user.

Twitter is where words reign supreme so it is no surprise that it went viral on Twitter and attracted just the audience that would appreciate what Wordle offered. The ability to check how much you knew, how far you could push yourself and bag some bragging rights along if you cracked the puzzle in those six tries.

Using the product makes you feel good without any guilt associated with it. I can’t think of a better way to share your results than a simple emoji matrix that you can simply copy-paste as a tweet. It stands out on the timeline and is easy to notice to incentivize users to generate organic word-of-mouth marketing for you.

From the perspective of NYT, it reflects well on how well they understand their target audience and know which business bets to take to continue surviving in a sector as challenging as traditional news media.In the end, I feel like the product was made such that it found just the channel to market itself organically, the users who loved using it, and an exit that most of us can only dream of.

References for the quoted sections:

https://www.afr.com/technology/why-on-earth-did-the-new-york-times-buy-free-puzzle-game-wordle-20220311-p5a411

https://www.axios.com/2022/05/04/new-york-times-earnings-wordle-acquisition-users